Some of my Massachusetts colonial ancestors were among the first of the westward migration, driven by the desire for land. As the grand narrative goes, Americans triumphed over Native peoples, buffalo herds and other forms of life to span the continent. Some of the early arrivals to the province of New York, settled in and stayed there for generations.

My research focused on the fraught and fascinating Barlow family, descendants of the Quaker-hating constable George Barlow, who left Sandwich, Massachusetts and moved to New York. As I followed the trail, I happened upon the following:

Holy mackerel! The Barlow I was looking at, is the above said “mother of Mr. H., an aged woman…” more easily recognized as Jemima (Barlow) Hitchcock. A daughter of Moses and Sarah (Wing) Barlow, and widow of Samuel Hitchcock, Jr. (1755-1806). Born in Amenia, Dutchess County in 1761 [1] and in 1837, living with her unmarried son, Gilbert, in Rensselaer County, when….

“At Schodack, N. Y. on the 3rd inst., Mrs. JEMIMA HITCHCOCK, widow of the late Samule Hitchcock, aged 75. The deceased was the mother of Mr. Gilbert Hitchcock, and one of the eleven persons in his family who were recently poisoned by arsenic mixed in the butter by a negro serving girl. After thirteen days of extreme suffering, she died from the effects of the poison., and has left a large circle of kindred and friends to mourn her loss.”[2]

Wow, Jemima was murdered, according to newspaper accounts by “a negro serving girl.” This particular description was often, was a gentle-sounding way to say, slave. Another issue is that “girl” might have meant a child, as we would assume in modern usage; “girl” might have described an adult. Who was she? Did she do it, and if so, why?

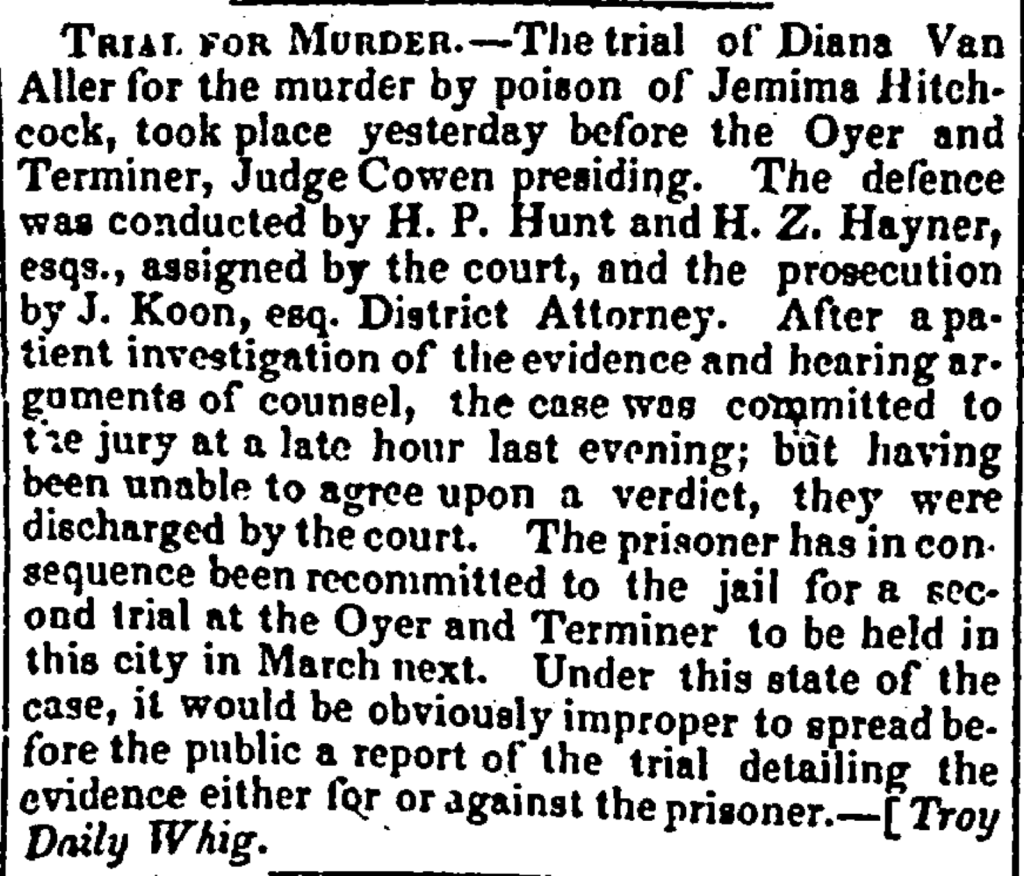

A Trial, but no details

The name of the accused is revealed, but this didn’t help with fleshing out this case. I looked for follow-up articles of the next trial and further news of the Hitchcock household, such as, did that second family member die or survive? I found nothing further of the Hitchcocks in the newspapers, but I did find a tiny item that confirmed the second trial took place and that a verdict was rendered.

So, Diana Van Aller or Dianna Van Allan was convicted and, presumably, was punished for the crime, which caused a death, but which the jury found was an unintended outcome. We can imagine, she was incarcerated for a time, where, when, and for how long, I don’t know. I found only one document which may record the accidental murderess.

In the 1850 US Federal Census for Troy, New York, living with a Williams family, is the following family:

Prince Vanaller – 50 – Black – Laborer – Born New York – Cannot Read / Write;

Diana Vanaller – 35 – Black – Born New York – Cannot Read / Write;

John H S Vanaller – 8 – Black – Born New York;

Catherine Vanaller – 5 – Black – Born New York;

Jane Vanransselaer – 80 – Black – New York – Cannot Read / Write. (3)

If this is the same person, Diana would have been born about 1815, making her about 22 in 1837, when she worked for the Hitchcock family and described in the above accounts as a “Black girl” and a “negro serving girl.” She might also have been Prince Vanaller’s (Van Aller) young wife.

If John and Catherine are her children, she would have been living with her husband in 1841 (as John was born about 1842). Perhaps, the sentence rendered in 1838 was for two years and Diana was released back to her husband. After 1850, Diana disappears. In the New York State census for 1865 (he was not found in the1860 US census), “Prince Vaneler” is still living Troy, a widower who was married twice.(4) Since Prince was 15 years older than Diana, it makes sense he had an earlier marriage.

If this is our Diana Van Aller, she died after the 1850 census and before the 1865 enumeration. We are left to wonder what happened and what was intended to happen the Hitchcock kitchen that fateful summer of 1837. Was it an innocent mistake? Was it revenge for mistreatment? Was it the doing of someone else altogether, meaning Diana was unjustly accused?

Poisoning was scandalous and popular

My newspaper database search for “poisoning,” from 1837 through 1847, turned up 421 results. The very same headline, “Attempt to Poison a Family,” was employed for other such incidents. In addition, the descriptive, “diabolical,” was clearly the journalistic go-to in this period for alleged intentional acts. Some of these poisonings were accidental (contamination) and some were substances mistakenly consumed. However, purposeful poisonings by wives and husbands, and “negro servants,” were not rare. Arsenic, the agent of Jemima (Barlow) Hitchcock’s death, mixes well, not only with butter, but ice cream, custard, tea, coffee, buckwheat cakes and, in one case, a jug of rum.

Sources:

- NEHGS, AmericanAncestors.org (AmericanAncestors.org : accessed 19 Feb 2018), George Barlow descendants. Rec. Date: 8 Apr 2016; The Register, Vol 172, Winter 2018; George Barlow, the Marshall of Sandwich, Massachusetts and his Descendants for Three Generations by Ellen J. O’Flaherty(concluded from Register 171, 2017).

- Commercial Advertiser (New York, NY), Thursday, August 10, 1837; Page 2.

- Ancestry.com; 1850 United States Federal Census; Year: 1850; Census Place: Troy Ward 1, Rensselaer, New York; Roll: 584; Page: 32a.

- Ancestry.com; New York, U.S., State Census, 1865. Rec. Date: 8 Jan 2016; City: Troy Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2014. Original data: Census of the state of New York, for 1865. Microfilm. New York State Archives, Albany, New York.

Resources:

GenealologyBank.com, Newspapers Archives Online ($ubscription service)