Early probate records for colonial Massachusetts show enslaved human beings, – men, women and children, in wills and estate inventories.

In my last post, I promised to tell to what else, besides the sweet bequests, I discovered studying the wills of Jonathan Slead (1703-1764) and his wife, Sibel (Tisdale) Slead (1701-about 1779), of the Bristol County town of Swansea, Massachusetts, and the title of this article says it all.

It’s sobering to discover one (or more) of your ancestors held fellow human beings captive, forced them to labor, and worse. Fellow fans of the PBS series, Finding Your Roots know what I’m talking about, – the moment Henry Louis Gates, Jr. provides a nice, clueless celebrity with documented evidence of an ancestor held fellow humans in bondage.

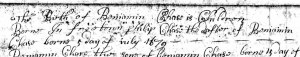

Jonathan Slead’s will, made February 8, 1764, is very long. He operated the Slade Ferry franchise, had lots of real estate, and was a wealthy man. Without children to take over, he had much to dispose of and conditions to be . The following excerpts are those germane to the topic:

————————————————————————————————————————–

I Jonathan Slead of Swansey in the County of Bristol and province of the Massachusetts Bay in Newengland, yeoman…

– I Give and Bequeath unto my well beloved wife Sibel : the Use and Improvement of one Half of this My Homestead farm ; and two thirds of All my household goods … My Negro Man Named Lot : and my Negro Garl Named peg : and my Negro Garl Named Mercy…

– I Give and bequeath unto my cousin Philip Slead son of my brother Edward Slead Deceased, that Orchard which I bought of William Slead which was formerly Robert Gibbs : And also my Negro boy named Daniel : to him the sd Philip Slead his heirs and assigns forever…

– I Give and bequeath unto Jonathan Slead son of my cousin William Slead Esqr Deceased : all that farm which I purchased of Pelatiah Majors : and which was former the sd Jonathans fathers farm : to him the sd Jonathan Slead I Give it and to his heirs and assigns forever : and the profits of sd farm I order to be Used for Educating the sd Jonathan until he arrives to Lawfull age. I also give the sd Jonathan My Negro Man named Isack … my Executor shall Diliver him the two cows and the mair and the Negro Man if Living…

– I give and bequeath to my two cousens namely Elizabeth peirce and Lydia Slead my Negro Garl Cate…

– I give to the two Daughters of my cousen William Slead Esqr Deceased namely Elizabeth and Rose Slead my Negro Garl named Luce …

– It is my will that my Negro Woman Mereah shall be free at my decease and have her bed and her cloths and to live in my house so long as she liveth : and if she should come to want then my will is that my Executor shall Support her comfortable so long as she Liveth…

– I Give and bequeath unto my couzen Samuel Slead son of my brother Edward Slead Deseased and to his heirs and assigns for ever all the Rest and Residue of this my homestead farm… after my wife hath don with it : And the fery boat and the privileg of the ferry : and also the one half of my boats… : and also four Negros namely Roger and Phillis and har two children Cofe [and] Mereah… (1)

————————————————————————————————————————–In addition to noting the eccentricities in spelling, were you counting? Jonathan names twelve (12) slaves, the “Negro” men, Lot, Isaac and Roger, women Mereah and Phillis, a boy, Daniel, “girls” Peg, Kate, Mercy, Luce and Phillis’s two children, Cofe and Meriah.

Notably, Jonathan directs that his slave, Mereah, be freed upon his death, allowed to live in his house and be comfortably supported until her own passing, differing significantly from the fates of the others. Lest you think this act is a sign of tenderness, consider that it is most likely Mereah was an older woman with little market value who might also have been nursing Jonathan’s through his illness and decline. A promise of freedom and support, might have guaranteed the quality of care Jonathan desired.

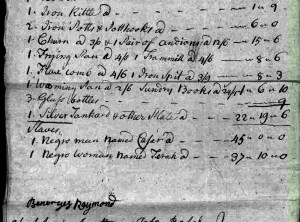

The Valuation

Swansea town records state, “Cpt Jonathan Slead Departed this Life November the 2:1764 In the Sixty Second year of his age.”(3) Shortly thereafter, appraisers, Jerathenal Bowes (or Bowers), Andrew Cole and William Brown went to work. They submitted an estate inventory to the probate court dated December 1, 1764. The salient excerpt is below:

…a Wood Boat cal’d Phenioc [£]65

A Negro Man Cal’d Lott £60

A Negro Man Cal’d Roger £63

A Negro Woman Cal’d Pegg £43

A Negro Woman Cal’d Mercy £35

A Negro Man Cal’d Israel [Isaac] £60

A Negro Woman Cal’d Phillice £45

A Negro Boy Cal’d Daniel £50

A Negro Woman Cal’d Kate £40

A Negro Girl Cal’d Lucy £37

A small Negro Boy Cal’d Cuff £20

A Negro Child Cal’s Merecah £6

A Pair Large oscen (oxen) £15

A Pair Staggs £14 8s…

one cow £4 10s

one cow £8…

Did Sibel do better?

Jonathan’s widow, Sibel (Tisdale) Slead lived nearly 15 years more, in the material comfort provided her. While the day she died isn’t known, the probate file for her estate is dated August 3,1779. The file contains the will Sibel made in 1771, when she bequeathed the silver spoons to her namesakes. As we know, she inherited the enslaved persons, Lot, Peg and Mercy from Jonathan. See the excerpts concerning them below:

————————————————————————————————————————— to my sister Phebe Winslow – my negro Girl named Mervey [Mercy]…

– to my negro man Lott, his Freedom, with all his wearing clothes & his Chest and all his things…

– to my negro woman named Pegg, her Freedom and all her wearing clothes, her Chest, and Bed and bedding and all her things… (2)

————————————————————————————————————————–It seems, Sibel appreciated the service (however coerced) Lott and Pegg provided her and “rewarded” them with their freedom (on her death). It’s also possible Lot and Peg were aged or ill, and cutting them loose from the estate would lower maintenance costs if they were unable to earn their keep.

I’d like to think Lot and Peg had many years ahead in which to enjoy their freedom, but while Sibel allowed them to take their clothes, a bit of furniture and personal effects, she gave them no money, no dwelling, no bit of land. Where were they to go? How were they supposed to live?

And then, there was Mercy, a “Garl” (girl) when Jonathan disposed of her in 1764, and still a “girl” seven years on, when Sibel wills her to her married sister, Phebe (Tisdale) Winslow and lastly,

————————————————————————————————————————— I will and order my Executor… to sell my negro man named Jace, and to give him the liberty to choose his Master and to deliver the money that said Jace sells for to my sister Phebe Winslow..

————————————————————————————————————————–

We learn that Sibel acquired another slave after Jonathan’s death. She chose to sell him away for cash. And how much “liberty” Jace (or any enslaved person) would have “to choose his Master” is debatable.

So, no, Sibel did not undergo a personal moral evolution, but movers and shakers in colonial Massachusetts were getting louder, championing freedom for in the years between Jonathan Slead’s death in 1764 and Sibel’s passing in 1779.

The Times were Changing

In 1764, the year Jonathan Slead (Slade) died, James Otis (1725-1783), a leading proponent of colonial independence, wrote in an influential pamphlet that “The colonists are by the law of nature freeborn, as indeed all men are, white or black.” (4)

Then in 1775, tired of being denied representation in government, and determined to make their own way in the world, Massachusetts men began to throw off the yoke that made King George III master. What did Sibel think of the conflict and the changes happening around her? Slade’s Ferry, once run by her husband and right on her doorstep, was targeted for capture by the British forces (the attempt failed).

Sibel was certainly not moved by the ideals of freedom for all, as evidenced by her continued enslavement of Lot, Peg, Mercy and Jace. She did not live to see who would win the war and may have believed her countrymen could never defeat Great Britain.

A Slade Abolitionist

Well to do Slade descendants continued to enjoy privilege as the young United States struggled with growing pains, including moral dissonance between stated ideals of freedom for all men and the continued practice of chattel slavery.

It took a while, but at least one Slade descendant was an activist for slavery’s abolition, and the great-great nephew of Jonathan and Sibel, Avery Parker Slade (1818-1889). An account of his funeral from The Boston Journal (18 Nov 1889) reads in part:

The services were conducted by the Rev. Mr. Howard of Somerset, assisted by Rev. E.[Edward] Edmunds of Boston and Rev. M. J. Talbot, D. D. [Micah J. Talbot] of Providence, R. I. both brothers-in-law of the deceased. Dr. Talbot’s eulogy of the deceased was particularly eloquent and impressive. In it he alluded to Mr. Slade’s pioneer labors in the causes of abolition and total abstinence, to his earnestness in education and agriculture, and to his generosity and his other noble traits. (5)

References:

(1) Jonathan Slead will. NEHGS, AmericanAncestors.org (AmericanAncestors.org : accessed 19 Jul 2021), Bristol County, MA: Probate File Papers, 1686-1880. Rec. Date: 8 Apr 2016; Probate Record 1765; Location Swansea, Bristol, Massachusetts, United States; Original Text Case Number 23481, Page 1 of 25; Volume Name Bristol 22000-23999, Page 23481:1Bristol County, MA: Probate File Papers, 1686-1880.

(2) Sibel Slead will. Ancestry.com. Massachusetts, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1635-1991. Rec. Date: 8 Jan 2016; Source Citation Probate Records 1687-1916; Index, 1687-1926 (Bristol County, Massachusetts); Author: Massachusetts. Probate Court (Bristol County) Description Notes: Probates, Vol 26, 1779-1781.

(3) Cpt Jonathan Slead Departed this Life November the 2:1764 In the Sixty Second year of his age. Massachusetts: Vital Records, 1620-1850 (Online Database: AmericanAncestors.org, New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2001-2016).https://www.americanancestors.org/DB190/i/13932/221/251748415

(4) Massachusetts Court System Guide – Massachusetts Constitution and the Abolition of Slavery

(5) NewsBank database and images, GenealogyBank.com (http://www.genealogybank.com/ : accessed 10 Aug 2021); Boston Journal (Boston, MA). Rec. Date: 28 Jan 2016; Boston Journal (Boston, MA); Tuesday, Nov 19, 1889; Vol: LVI, Issue:18529, Page 3.

Resources:

History of Bristol County, Massachusetts, with biographical sketches of many of its pioneers and prominent men; Dwayne Hamilton Hurd; 1883. (Digitized at Archive.org)

PBS – Finding Your Roots with Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Massachusetts Court System Guide – Massachusetts Constitution and the Abolition of Slavery

Wikipedia – History of Slavery in Massachusetts

History of Massachusetts Blog – Slavery in Massachusetts

American Creation – James Otis: Abolitionist