I am luckier than most in nailing down origins for Irish immigrant ancestors, but not all of them. I have quietly uttered impolite words on reading, “born in Ireland,” on a new-found record.

I am luckier than most in nailing down origins for Irish immigrant ancestors, but not all of them. I have quietly uttered impolite words on reading, “born in Ireland,” on a new-found record.

My great-grandfather, Thomas Francis Dolan’s was born in County Roscommon, Ireland, [1] but with parents, John and Ann, and the common surname, DOLAN, I may never learn my Dolan ancestral townland. However, discovering Thomas had a brother who came to him in Boston, let me add another branch to the family tree.

I’m slightly embarrassed tell you that my great-granduncle, Martin Dolan, was right there all along but, laser-focused on my direct line (Thomas), rendered Martin invisible! He was listed on the page with Thomas, on Jewett Street in Jamaica Plain (Boston, MA) in 1893 [2] and 1894 [3]. Both men were also employed as plasterers. The identity-clincher was Martin’s 1895 marriage record that gave parents’ names, John and Ann Dolan, matching up with Thomas. [4]

Also, I should have been quicker to suspect the “Mortimer Dolan” who witnessed Thomas & Bridget Dolan’s marriage (1890), was actually, Martin! Note: This reaffirms the value of the FAN Club (Friends, Associates, Neighbors) approach to the ancestor hunt.

Becoming an American

Martin disembarked in Boston on April 14,1886, when he was 16 years old. His elder brother had arrived there in 1874, when he was only eleven. Thomas had a dozen years of Boston living experience. Martin had lived five years longer than his brother in the land of his birth.

Was Thomas was at the dock to meet Martin? Was there communication between Roscommon and Boston? Did Thomas expect his brother, or did Martin find his own way through a strange city to his brother’s door? At this remove, there is no way to know.

At any rate, Thomas proved himself a good brother. He provided Martin a place to live and helped him learn a skilled trade (plaster work), rather than having to take one of the dangerous, back-breaking and lowest-paid jobs that countless Irish laborers were forced to take. Thomas became a citizen of the United States in 1887 and guided Martin through the process finalized in 1893. [2]

As Roman Catholics, Thomas and Martin would have certainly attended Sunday Mass at the parish church. They might have attended church events to socialize. The young bachelors were certainly interested in meeting nice, unmarried, Catholic girls.

Thomas found his lady first, a later immigrant arrival named Bridget Dolan. (Yes, she had the same surname as Thomas, and was born in County Roscommon, too!) As mentioned above, at their marriage in St. Thomas Aquinas Church (1890), Martin stood up for his older brother. It also appears he stayed on, living and, probably, working with his brother. Bridget kept house, did laundry, cooked meals, and gave birth to two children in the five years before Martin found a wife and became a householder himself.

The Brothers’ Paths Diverge

Thomas Dolan made but two big moves in his adult life. He left the plastering trade when he was hired by the City of Boston in 1906, and stayed until his retirement. [5] And Thomas relocated his family just once, leaving Jewett Street (Jamaica Plain) for a house on Brown Avenue, (Roxbury) where he lived until his death. By contrast, Martin Dolan continued to work as a plasterer until 1916. [6] However, he had eight residential addresses between the years 1895 and 1920, that’s a lot of instability for a family.

Martin Dolan married Rose Duffy, at the Church of the Assumption in Brookline, Massachusetts. [7] They embarked on married life, as couples still do, confident that love and faith, woould see them through. Ten months later, Martin and Rose added a new leaf to the family tree; this was Mary Ann (1896), followed by Helen (1898), Anna Teresa (1900) and Edward James (1903) who all grew to adulthood. In 1906, a tiny girl, named Rose, for her mother, failed to thrive and died at six weeks.

Such a tragedy would be hard on any family at any time, but during these years, Martin had moved Rose and the children, a number of times. The anchoring parish church changed, too. The two eldest daughters were baptized in Our Lady of Perpetual Help. In 1900 through 1903, they were attending All Saints. The infant Rose was baptized at St. Francis de Sales (1906).

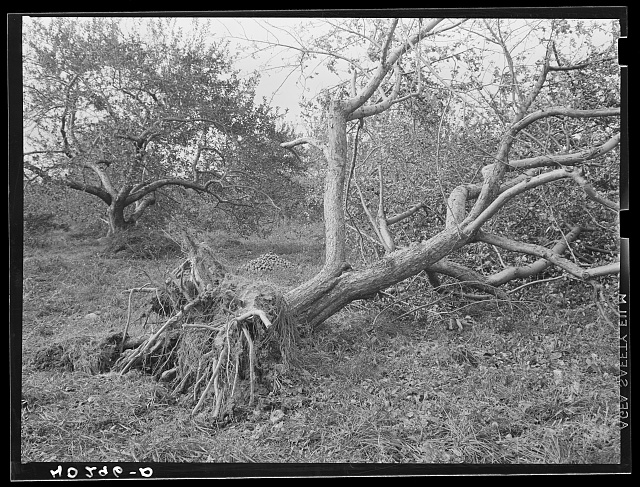

Evidence of crisis at home is revealed by the 1910 US census, in which Martin absent and Rose Dolan enumerated as head of household and married 16 years. To support herself and the four children, Rose worked as a laundress, at the time, difficult and backbreaking labor. [8] Where Martin was in 1910 and what he was doing with himself remains unknown.

For the 1920 US census, Martin was back as head of household. He was listed as 47 years old and working, not as a plasterer, but as a shipper for a drug factory and Rose was back to keeping house for Martin and three of their four surviving children: Mary (23 and married), Edward (16) and Annie (19). [9] Helen Dolan wed in 1918 and was living with her spouse, John Hannon. [10]

In May 1926, Martin Dolan died at 56 years of age. He had some problems that were swallowed up by the passage of time. But he was blessed to see each of his children married. Martin rests in Mount Benedict Cemetery, in the plot the family obtained for their infant daughter, Rose, 20 years before. [11]

Epilogue

That might have been the end of my tale, but for my reluctance to omit the fate of Martin’s widow. Rose (Duffy) Dolan stayed in the rented apartment she shared with Martin on Webber Street, Roxbury; it may have been the same place she and the children were living in 1910. In 1948, her children were busy raising families and Rose, now in her seventies, was living alone. After having weathered a stint as mother and breadwinner, living through the first world war, the influenza pandemic, the Great Depression, and the second world war, The Boston Traveler of November 13, 1948, reported:

Hub Woman, 77, Critically Burned

Mrs. Rose Dolan, 77, of Webber street, Roxbury, was critically burned this noon when flames from a flooded kitchen oil range ignited her clothing.

Her Grandson-in-law, William Estano, 21, of Hampden street, Roxbury, received burns on the arms and hands as he came to her rescue and smothered the flames.

Mrs. Dolan lives alone in her third floor flat and Estano and his wife Helen, 20, were assisting the aged woman with her housework when the accident occurred. Mrs. Dolan was taken to City Hospital by police and her name was placed on the danger list. She received third degree burns. Estano was treated at the hospital and released.

Rose died of her injuries two days later. She joined Martin and little Rose in eternal sleep at Mount Benedict.

Rose’s heroic grandson, William Estano, (spouse of her granddaughter, Helen Hannon), recovered. He lived to survive his wife Helen’s passing in 1988. Not only that, he learned to love again, in his 60s, before he went to his own rest at the age of 81.

i

Sources

[1] Ancestry.com; Massachusetts, Petitions and Records of Naturalizations, 1906-1929; National Archives at Boston; Waltham, Massachusetts; ARC Title: Copies of Petitions and Records of Naturalization in New England Courts, 1939 – ca. 1942; NAI Number: 4752894; Record Group Title: Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1787-2004; Record Group Number: RG 85: Petitions, V 148, 1887-1888.

[2] Ancestry.com; National Archives at Boston; Waltham, Massachusetts; ARC Title: Petitions and Records of Naturalization , 8/1845 – 12/1911; NAI Number: 3000057; Record Group Title: Records of District Courts of the United States, 1685-2009; Record Group Number: RG 21: Naturalization Records, No 235-40 to 239-102, 26 Nov 1892 – 27 Sept 1893.

[3] Ancestry.com; U.S. City Directories; Boston, Massachusetts, City Directory, 1894.

[4] Ancestry.com; Massachusetts, U.S., Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988; Boston, Massachusetts; Out of Town Marriages, 1893-1895.

[5] MyHeritage.com; Massachusetts Newspapers, 1704-1974; The Boston Post (Boston, MA); Friday, June 7, 1935; Page 7 of 32: City Retires 13 Employees.

[6] FamilySearch; “Massachusetts, Boston Tax Records, 1822-1918”, (https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:68S6-44N1 : 23 August 2021), Martin Dolan, 1916.

[7] Ancestry.com; Massachusetts, U.S., Town and Vital Records, 1620-1988. Marriage Place: Boston, Massachusetts; Title: Out of Town Marriages, 1893-1895.

[8] FamilySearch; 1910 United States Federal Census; Roll: T624_620; Page: 11A; Enumeration District: 1508; FHL microfilm: 1374633.

[9] Ancestry.com; 1920 United States Federal Census; Roll: T625_735; Page: 6A; Enumeration District: 330.

[10] FamilySearch; “Massachusetts Marriages, 1841-1915,” Boston, Suffolk, Massachusetts, United States, State Archives, Boston; FHL microfilm 828,894.

[11] Boston Catholic Cemetery Association; https://search.bostoncemetery.com/

![H.A. Thomas & Wylie. (ca. 1896) Man Wearing Tuxedo, Holding Bowler Hat. , ca. 1896. [N.Y.: H.A. Thomas & Wylie Litho. Co] [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress](https://pooririshandpilgrims.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/1896-boweler-tuxedo.jpg?w=230)